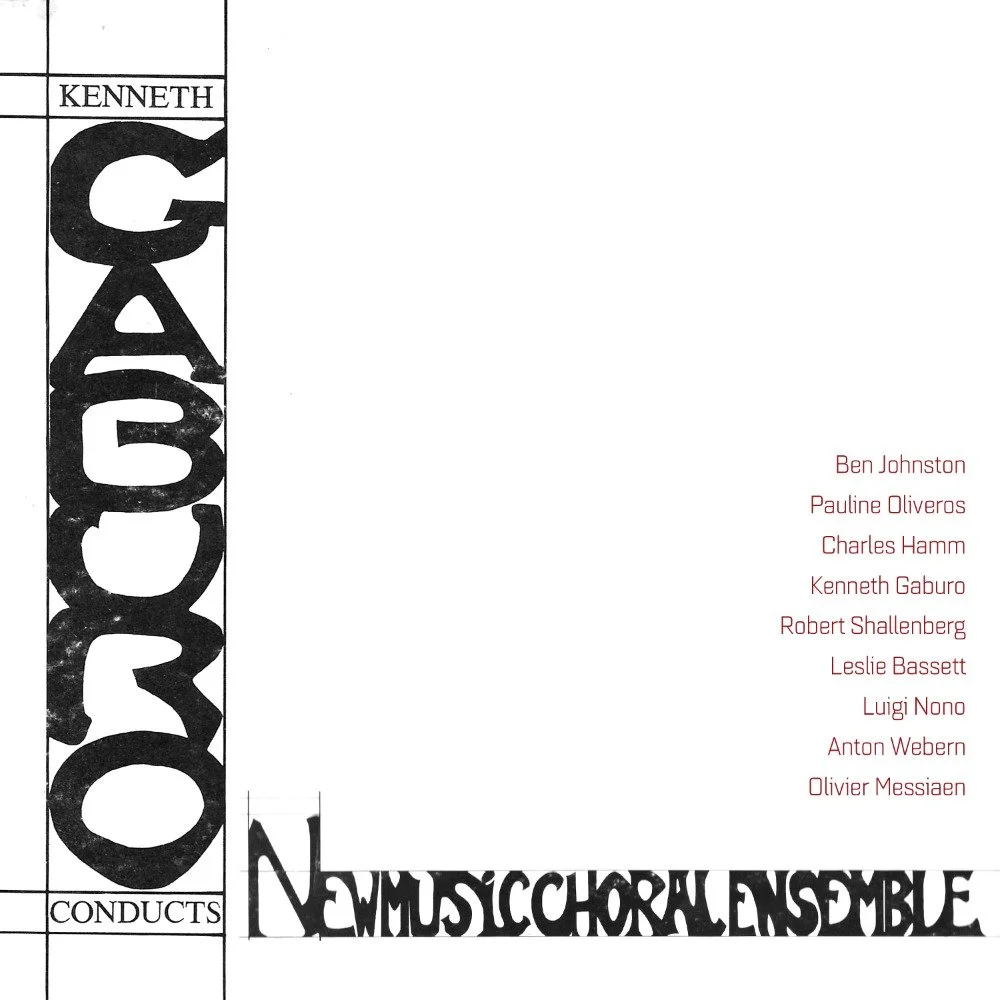

Kenneth Gaburo conducts New Music Choral Ensemble 1

Kenneth Gaburo conducts New Music Choral Ensemble 1

1. Ben Johnston 3:26

2. Pauline Oliveros 3:21

3. Charles Hamm 5:03

4. Kenneth Gaburo 3:51

5. Robert Shallenberg 3:18

6. Leslie Bassett 2:10

7. Luigi Nono 7:02

8. Anton Webern 2:29

9. Kenneth Gaburo 4:38

10. Olivier Messiaen 18:02

TOTAL TIME: 53:25

The Ensemble

Soprano

Barbara Dalheim

Rosalind Powell

Jean Geil

Margaret Rosso

Jo Ann Lacquet

Patricia Hawkins

Alto

Marcia Swengel

Bonnie Barnett

Shirley Panish

Karen Hinshaw

Miriam Barndt

Barbara Shapiro

Tenor

William Brooks

Albert Hughes

Doug Pummill

Robert Smith

Bass

David Barron

Richard Hanson

Philip Larson

Lawrence Weller

Brian Winter

David Correll

Charles Braugham, drums

Thomas Frederickson, bass

Restored and mastered by David Dunn from live concert tapes (1967) Produced by Philip Blackburn

Thanks to: Bill Brooks, Bonnie Barnett, and Al Margolis

Of all the areas of recent [1969] musical activity, the field of choral music seems to have been the most conventional, prejudiced, and neglected. Even as late as 1965 with instrumental music and performance reflecting the deepest kind of innovation and exploration, with the flowering of electronic music, com puter development, and the emergence of mixed media, choral music performance in particular, lagged far behind. An extensive literature was clearly there (even though we have yet to see its ultimate devel opment, unique and typical of its own genre as distinct from instrumental music from which it generally still derives), but except for occasional performance by ad hoc groups, no ensemble to my knowledge could afford the luxury of devoting itself completely to the new choral music, over a sustained period of time in order to get at more intrinsic values. There were other prejudices. Apparently, choral music connotes something else (eg, after a concert at Purdue University in 1967, someone remarked, “If I had known it was going to be that kind of choral program I would certainly have invited my more sophisti cated friends”). Attitudes of singers didn’t help, and choral directors seemed to have their own set of problems, eg,

“Among the major developments, it was good to see the rising interest in contemporary cho ral composition. Kenneth Gaburo and his Experimental Music Ensemble from the University of Illinois gave what one would assume were perfect renditions of a half dozen fiendishly difficult pieces. At times it seemed as if the music were written against the chorus instead of for it. The obvious necessity for vocal superstars caused many directors in the audience to react with dis may and concern. Works such as Luigi Nono’s “Sara Dolce” performed by an octet instead of the entire group of 16 singers, had exposed entrances in both extremes of range and at all dynamic levels. The resulting sound was more machine-like than vocal. It was human electronic music.

This does not mean it was not valid music. What it does mean is that composers must find ways of writing such music for the general consumption of less talented performers. On the other hand, choral conductors must be willing to learn about such music, and not allow a seg ment of music to die by default.”

—Jack Boyd, Music Educators Journal

October 1966, ACDA Convention.

Taking a wide spectrum of accounts into consideration, there simply seemed to exist in the final analysis, a general feeling that the voice was a very limited phenomenon, unreliable, and possibly not as interest ing with regard to exploration as were other sound domains.

In this context, it is possible that the New Music Choral Ensemble, itself, was a luxury. That is, we worked out things in our own time without pressure of commerce, politics, or academia—elements which so of ten determine the quality and/or the very existence of performing groups. We were quite autonomous. I am prepared to believe that the absence of the aforementioned conditions resulted in something of

rare value. In any case, such freedom enabled us to devoted full attention to the complexities of the New Music, to represent the composer properly, to consider and develop criteria necessary to defining the ensemble sense, to encourage new literature especially by demonstrating the enormous range of vocal expression and techniques available, and to flourish in a highly cultured environment such as existed at the University of Illinois.

The ensemble was fortunate in having some summer support variously from the University of Illinois School of Music and Graduate Research Board, and the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, although I hasten to add that is was the spirit of those young people in the group, their involvement and commit ment to performance, and their progressive enthusiasm for contemporary music that kept the ensemble alive. It was during these summer periods that we were able to concentrate daily on learning the litera ture. In three years the ensemble included 40 works in its repertoire and as many performances. We went about things systematically, amd looked for works which imposed serious performer-perceptual difficulty as a result of the composer’s further exploration of the regions of pitch, duration, timbre, inten sity, etc., and included works which employed new notational systems, unconventional tuning systems, indeterminate elements, unusual instrumental-vocal techniques, and performer/electronic-sound media. In the end, the distance we had come in the development of choral sensibility was rather staggering. Furthermore, the total array of work accomplished as of that moment in time established the phenom enal extent of vocal flexibility and left clearly for the future other paths to follow. Necessarily, this single recording falls short of that larger representation although the contents are as distinct from each other as octaves (Ives [not included here]) are from microtones (Johnston = 31 pitches to the octave), as ex treme registral fragmentation on many parameters (Nono) is from more conventional SATB distribution (Webern), as imaginative language (Oliveros = sound per se, Messiaen = French and pseudo Hindu) is from compositional linguistics (Shallenberg).

The ensemble proceeded from one basic assumption which was to be flexible enough to meet the com plex demands which each work uniquely made, as contrasted with typical choral convention that devel ops a group “sound” (frequently by way of a priori rules of operation) which is imposed on each work performed. In the latter case such a process often acts as a filter upon peculiar properties a given work may structurally possess, and furthermore renders all works performed in that manner non-distinct except for surface elements. Contrarily, in the former case the structure of a work may require that consonants be emphasized over vowels, that sopranos not sound as one on a given line, that qualitative resonant distinctions within a phonetic class be made, (eg, degrees of nasality), that word accents don’t correspond to metrical accents, that phonetic “harmonic” movement is more important than textual intelligibility, etc.

All of the members of the group had extensive vocal training, but they were not all singers in the con ventional sense, nor, for that matter, were they superstars. While there were some elegant members who were clearly able to bridge the apparent dichotomy between operatic singing and the requirements of new music, there were also other elegant members whose main life emphasis was on composition, conducting, musicology, library science, theory, and music education (parenthetically, this richness itself brought unique properties to the music, and ultimately provided the basis for a more current assump tion of NMCE III, which is to require that members be multi-talented).

… By the time the ensemble had worked together for three years, it was axiomatic that a performance was a performance. In this sense comparatively few distinctions had to be made between a recording session and a public performance, between a rehearsal and a music history classroom presentation, or for that matter, between an audience present and an audience absent (the most outstanding example of the latter situation obtained in an afternoon concert at the Expo 67 Youth Pavilion, when, save for an occasional looker-in as if we were on exhibit, there literally was no audience. The demoralizing aspect of this situation simply resulted in one of the best performances we ever gave).

The thing about the singers is that they are completely at home in the idioms. And so they are totally convincing. In Pauline Oliveros’s Sound Patterns they counterpoint hissing, clicking, yawn ing, and other vocal non-singing sounds. After a bit, one understands how percussion instruments came to be. Then in Charles Hamm’s Round, a man walked from the audience to sit near a coat-rack looking thing with a circular band of music on top. He turned it on. Then, one after another, seven singers came to stand around it and begin singing when the break in the circle got to them. Then a tape, instant replay, canonized the proceedings. At the end they left, almost one by one, and only the frantic tape was left.

—Phyllis Dreazen, Chicago Tribune 3/30/68

—Kenneth Gaburo

La Jolla, California, 1969